23 Surgical Indications for Pituitary Tumors

Marcello D. Bronstein

Introduction

Introduction

Pituitary tumors are frequently occurring neoplasms, accounting for 10 to 15% of all intracranial neoplasias in surgical material and being found in up to 27% of nonselected autopsies.1 They present with a broad spectrum of biologic presentation. Although almost invariably benign (adenomas), up to 20% of pituitary tumors exhibit invasive behavior. The exceedingly rare pituitary carcinomas do not diverge from adenomas by histologic features; distant metastasis is the sole diagnostic criterion.2

Pituitary tumors ate classified according to their morphologic and functional characteristics (Table 23.1). Such neoplasms are named secreting or “functioning” when they produce hormones in sufficient amounts to lead to clinical manifestations, including, from higher to lower prevalence, lactotrophic tumors (prolactinomas), somatotropinomas (acromegaly, gigantism), corticotropinomas (Cushing’s disease), and, rarely, tumors secreting the glucoproteic hormones thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) (thyrotropinomas: secondary hyperthyroidism), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (gonadotropinomas). Pituitary adenomas can also secrete two or more hormones, growth hormone (GH) and prolactin (PRL) co-secretion being the more prevalent of them. Pituitary neoplasms that do not produce circulating measurable amounts of intact hormones are called nonsecreting or nonfunctioning (NF) tumors.3

| Based on Morphology | Based on Function |

Microadenomas Enclosed Invasive Macroadenomas Enclosed Invasive Expanding | Secreting Prolactin (PRL): prolactinomas Growth hormone (GH): acromegaly/gigantism Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): Cushing’s disease Follicle-stimulating hormone/luteinizing hormone (FSH/LH): gonadotrophic tumors Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): central hyperthyroidism Mixed (mainly GH/PRL) Nonsecreting (clinically nonfunctioning) |

Regarding their morphology, pituitary tumors are classified as microadenomas (less than 10 mm in diameter, generally enclosed, less frequently invasive) and macroadenomas (enclosed to sellar boundaries, expansive, or invasive (Table 23.1).4 Microadenomas usually are diagnosed by the clinical picture or as a consequence of their hormonal hypersecretion or, when NF, by incidental findings from imaging performed for another indication, such as head trauma, or by autopsy finding. Macroadenomas are diagnosed by hormonal hypersecretion as well as hyposecretion, when present, or by neuro-ophthalmologic and neurologic manifestations. They can also be incidentally found.1 Although there are no histologic differences, invasive tumors grow faster, leading to sellar erosion and infiltration of neighboring structures, such as the dura mater, bone, and sphenoid and cavernous sinuses. The morphology of pituitary tumors is assessed by imaging, and confirmed by surgery and pathology. Sometimes it is difficult to assess the degree of tumor invasiveness, as pituitary adenomas do not present a true capsule, just a “pseudocapsule” formed by pituitary cells and the reticulin network. Therefore, although invasiveness is more associated with macroadenomas, it can also be present in microadenomas.

The results of a surgical approach to pituitary adenomas depend not only on the surgeon’s skill, but also on the tumor’s features. A microadenoma or an enclosed macroadenoma has a much higher probability of cure than does a giant invasive tumor. Moreover, efficacious medical therapies, both for hormonal and tumor volume control, become the first-line treatment for pituitary tumors, especially prolactinomas and somatotropinomas, and mainly for those tumors that are not candidates for surgery. Nevertheless, surgical treatment, mainly by a microsurgical or endoscopic transsphenoidal approach, persists as a mainstream treatment for pituitary tumors. Its indications for each type of tumor are described in the following sections.

Secreting Pituitary Tumors

Secreting Pituitary Tumors

Prolactinomas

Prolactin-secreting adenomas are the most prevalent pituitary tumors.5 An analysis of 50 surgical series by Gillam et al6 encompassing 2137 microprolactinomas and 2226 macroprolactinomas found overall remission rates of 74.7% and 33.9%, respectively. Moreover, recurrence was observed in 18.2% of microadenomas and 22.8% of macroadenomas. Therefore, the overall surgical control for macroadenomas is far from ideal. On the other hand, prolactinomas respond very well to dopamine agonist (DA) drugs, such as bromocriptine and, especially, cabergoline; both PRL normalization and tumor shrinkage are observed in up to 80% of cases, including invasive ones, that are not candidates for surgery.5 Additionally, a significant number of patients persist with normal serum PRL levels after DA drug withdrawal.7 Nevertheless, medical treatment with DA also has disadvantages, mainly intolerance and resistance. Therefore, prolactinomas have the following surgical indications:

1. Failure of medical therapy (intolerance/resistance): 20% of cases

2. Patient’s personal choice (microprolactinomas)

3. Tumor enlargement on medical therapy: rare

4. Unstable pituitary apoplexy: 10% of cases

5. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage during dopamine agonist therapy8: rare

6. Optic chiasm herniation on dopamine agonist therapy: rare

7. Previous pregnancy complicated by tumor expansion9

8. Symptomatic tumor enlargement during pregnancy that does not respond to reinstitution of dopamine agonist treatment9

Acromegaly

This disabling and rare disease, with a prevalence of 38 to 69 cases/million inhabitants, is almost invariably caused by a GH-secreting pituitary adenoma. About 10% of cases occur before adulthood, leading to gigantism. The life expectancy of acromegalic patients is reduced by about 10 years, and mortality, mainly due to cardiovascular complications, is three times higher than in the general population. Therefore, an aggressive approach to normalize GH/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is needed. Fortunately, many treatment modalities are currently availably for acromegaly (Table 23.2).10

• Pituitary surgery • Medical therapy o Somatostatin analogs o Dopamine agonists o GH-receptor antagonist • Radiotherapy |

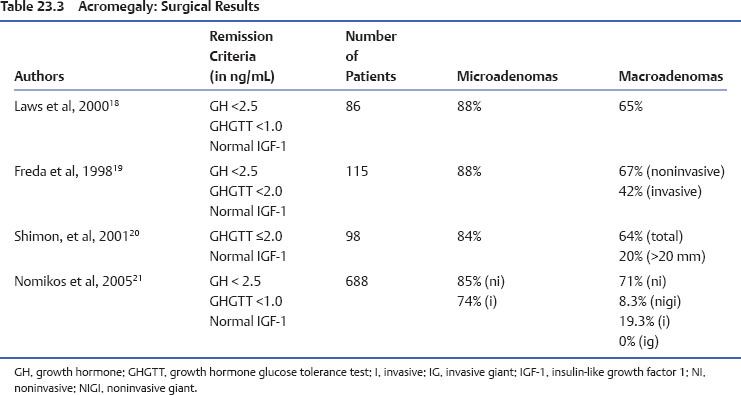

Surgery, mainly by the transsphenoidal route, remains the first-line treatment for acromegaly. The main advantages are prompt results, the possibility of a definitive cure, resolution of the mass effects, and tumor debulking, which may improve further medical therapy. However, there are also disadvantages, such as the lack of availability of skilled surgeons, poor results in large/invasive tumors, the risk of complications (hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, CSF leakage), the 10% recurrence rate, and the comorbidities-dependent anesthesia and surgery risks. An analysis of four important surgical series encompassing all kinds of GH-secreting adenomas found, as expected, better results in microadenomas and enclosed macroadenomas, and overall surgical control in 57% of cases (Table 23.3). Therefore, acromegalic patients harboring large/invasive tumors may be primarily medically treated, mainly with the somatostatin analogues octreotide LAR and lanreotide autogel,11 which are able to control GH/IGF-1 secretion in approximately 60% of cases but also lead to tumor shrinkage in up to 80% of patients. Furthermore, debulking surgery may improve the response to somatostatin analogues in resistant cases.12 Also DA and the GH receptor antagonist pegvisomant have a place in the acromegaly treatment algorithm. Radiotherapy, in addition to the long latency period required to achieve disease control, presents a high incidence of complications (hypopituitarism, radionecrosis, secondary tumors, cerebrovascular disease, cognitive disturbances) and is currently reserved for only invasive/resistant cases.13

Cushing’s Disease

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting microadenomas are the main cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Similarly to acromegaly, Cushing’s disease is associated with many comorbidities and increase mortality rate. Therefore, early and efficient therapy is highly desired.14 Transsphenoidal pituitary surgery is the first-line treatment. According to the main published microsurgical series, it leads to disease control in 60 to 80% of cases (<15% for macroadenomas), with a recurrence rate of up to 20%.14 The transsphenoidal endoscopic approach presents results comparable to the best microscopical approaches. The recurrence rates are apparently lower, but longer follow-up is needed to confirm this finding.15 In addition, the endoscopic approach may be a good option for reoperation of patients with recurrent or persistent Cushing’s disease.16

In cases of surgical failure, other therapies are available:

• Drug therapy: directed to the pituitary or the adrenals. Many drugs are available, but the success rate is relatively low, with a high incidence of side effects.14

• Radiotherapy: both conventional and stereotactic. With better results in children, radiotherapy presents the same problems described earlier for acromegaly.

• Bilateral adrenalectomy: although almost always curative, it requires lifelong glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement, and may lead to Nelson syndrome in a significant number of patients.

Clinically Nonsecreting (Nonfunctioning) Pituitary Adenomas (NFPA)

In these tumors, no hormone is secreted in excess, so the clinical features are related to the macroadenoma mass effect, and mainly include visual disturbances, headache, and hypopituitarism. Both micro- and macroadenomas can also be incidentally diagnosed. Therapy is indicated to relieve the tumor compression, when present, or to prevent future mass effects or the chance of pituitary apoplexy.17 The surgical approach is the most effective treatment for NFPA. Radiotherapy is indicated to prevent tumor regrowth when tumor remnants are significant, but poses the problems already described. Drug therapy for NFPA is an emerging field, but still presenting poor overall results.17

References

9. Bronstein MD. Prolactinomas and pregnancy. Pituitary 2005;8:31–38

10. Ben-Shlomo A, Melmed S. Acromegaly. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2008;37:101–122, viii

< div class='tao-gold-member'>