5 Transnasal Surgical Approaches for Skull Base Lesions

Eduardo Vellutini, Aldo Cassol Stamm, Shirley S.N. Pignatari, and Leonardo Balsalobre Filho

Introduction

Introduction

Since the introduction of modern endoscopic surgical techniques, transnasal endoscopic skull base surgery has been indicated for the management of lesions located from the cribriform plate to the clivus and C2, showing low rates of morbidity and mortality.1–5

Endoscopic surgical treatment approaches for the majority of skull base lesions usually requires entering the sphenoid sinus, the most posterior of the paranasal sinuses. To enter the sphenoid sinus through the nose, knowledge and understanding of the nasal cavity and sphenoid sinus anatomy, physiology, and function are paramount. It is always important to remember that the sphenoid sinus presents close anatomical relations to important structures, such as the optic nerves, the internal carotid arteries, and the cavernous sinus.

Several surgical approaches to the sphenoid sinus have been proposed over the years, both microscopically and endoscopically. From sublabial, to transoral, to fully endoscopic transnasal approaches, much has been described.

Most of the surgical approaches developed in recent years have focused on how to avoid the most frightening complications usually related to surgeries, such as vascular and neural injuries, cerebrospinal fistula (CSF), and meningitis.

However, little attention has been given to a very important part of this surgical approach—the nasal step. Although not life threatening, some nasal complications, such as epistaxis, septal perforation, infection, and nasal obstruction, are situations that frequently lead to impairment of the patient’s quality of life.

Moreover, the type of nasal approach will determine whether it is possible for the surgeon to use both hands in performing the surgery, and whether it is possible to do a cranial base reconstruction with pedicle nasal mucosal grafts. As there is a wide range of lesions in different topographies that can be treated by transnasal endoscopic surgery, the type of nasal approach as part of the procedure should be chosen individually for each patient according to the lesion’s location, size, and complexity, and the need for skull base reconstruction.

If the proposed endoscopic skull base surgery is not complex, it can usually be performed by just one surgeon, and in most cases less invasive approaches are preferable. In contrast, complex lesions more often require two surgeons and a four-hand technique. In these cases, the surgical approaches are usually more invasive, with a higher chance of producing sinonasal complications and sequelae.

The introduction of the endoscope in skull base surgery facilitated the adaptation of the classic nasal surgical approaches, such as the transnasal-transseptal and direct transnasal, to a nonspeculum type of surgery. The transnasaltranseptal surgical approach allows better preservation of the nasal mucosa; however, because the approach is accomplished by using a single nostril, it does not permit the two-hand technique. In contrast, the direct transnasal approach, although creating more injury to the nasal mucosa and turbinates, allows the use of two nostrils after the resection of the posterior part of the nasal septum.

These two surgical approaches are usually sufficient to resect a wide range of tumors; however, due to the progress of endoscopic techniques in addition to the development of more complex surgeries, particularly those beyond the paranasal sinuses extending into the dura and cavernous sinus, it has been necessary to review the classic surgical approaches and to seek complementary procedures. In addition, the still significant rates of persistent CSF fistula related to the surgeries has driven surgeons to develop new approaches, combining a large exposure of the surgical field with the possibility of creating vascularized mucosal flaps, facilitating the reconstruction of the cranial base defect.6 In complex surgeries, preoperative planning of the reconstruction step always plays an important role in determining the best surgical access.

The precise knowledge of the patient anatomy provided by imaging exams is also important when determining the best surgical approach. Computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential for characterizing the morphologic aspects of the sphenoid sinus, for identifying its anatomical relationship with the internal carotid artery, optic nerve, cavernous sinus, and Onodi cells, and for determining the precise location of the lesion or tumor and its relationship with other important anatomical structures including the paranasal sinuses, skull base, and ethmoidal arteries. This chapter describes the transnasal surgical approaches that are most often used today.

Transnasal Direct (Unilateral) Approach

Transnasal Direct (Unilateral) Approach

Indications

This surgical approach is usually indicated for lesions that do not need a wide exposure or a special skull base reconstruction. It can be used to treat patients with small unilateral CSF fistulas in the sphenoid or ethmoid sinuses and patients with unilateral medial orbital decompression.

Surgical Technique

The surgery is performed through a single nostril. If the nasal cavity is too narrow and the passage of the endoscope and operating instruments is limited because of a septal deviation, a septoplasty should be done first.

After identification of the middle and superior turbinates, the posterior region of the nasal septum, and the choanal arch, the ostium of the sphenoid sinus is probed with a seeker/palpator. The ostium lies superiorly to the choanal arch between the superior turbinate and the septum. To improve access to the posterior ethmoidal cells and to the sphenoid sinus, the superior turbinate can be removed. Exceptionally, the posterior portion of the middle turbinate can also be removed.

Following the identification of the sphenoid ostium, if the lesion is located within the sphenoid sinus, the anterior wall of the sinus is then opened, starting from the ostium region. The sphenoidotomy is carefully enlarged inferiorly, avoiding damage to the posterior septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery that crosses the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus at this region. If both sphenoid sinuses need to be surgically exposed, the mucoperiosteum of the anterior wall and the sphenoid rostrum are displaced laterally and reserved for posterior reconstruction if necessary. The anterior wall, sphenoid rostrum, and all intersinus septa are resected, giving wide exposure to the sinus (Fig. 5.1).

This surgical approach is preferred mainly for the treatment of unilateral lesions. The advantages of this approach are that it provides direct access and it preserves most of the anatomical structures in the nose and the physiology of the nasal cavity. The disadvantage is the inability to work in both nostrils simultaneously by two surgeons.

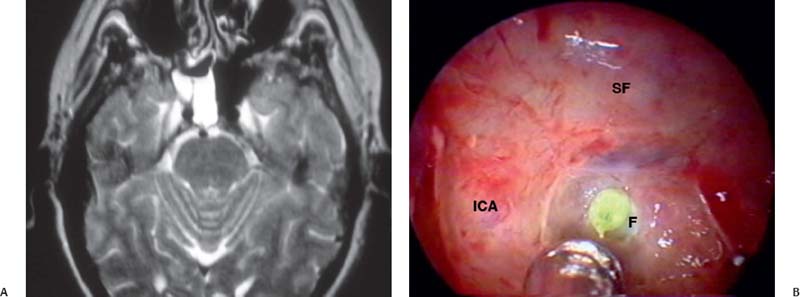

Fig. 5.1 (A) Magnetic resonance imaging of cerebrospinal fluid filling the right sphenoid sinus. (B) Intraoperative view through a direct nasal approach demonstrating the fistula in the right clivus, under the floor of the sella. F: clival fistula; ICA: internal carotid artery; SF: sellar floor.